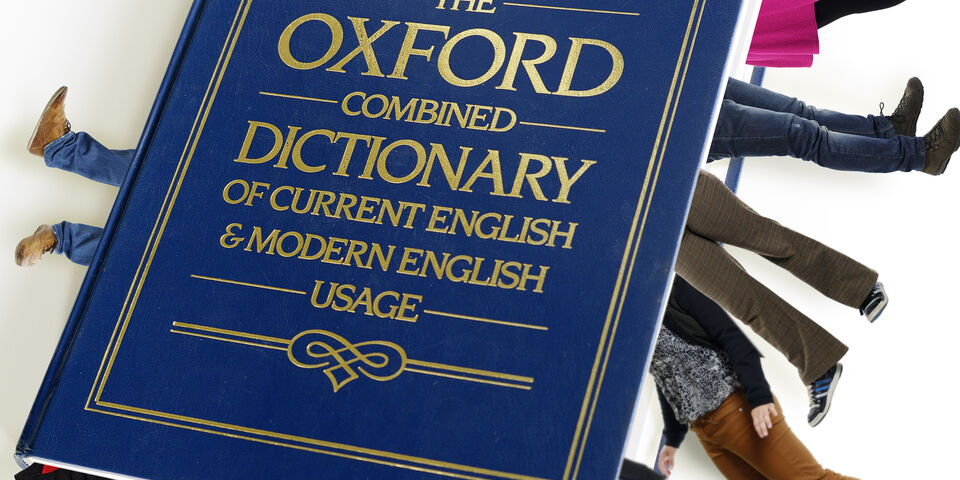

The Global Language

As you sit in your classes and listen to your professors lecture in English (hopefully, without too many Dutchisms) you may wonder why exactly English has become the lingua franca -a shared language used by speakers of different native tongues- of the scientific and academic world (and business and diplomacy and … the list goes on and on…). Why not French, German or, gosh, even Dutch? And while it’s useful to be able to communicate with people from disparate linguist backgrounds, are there any disadvantages to switching to one common language?

Sprechen Sie Deutsch? Ou Français?

More than 98 percent of all scientific articles published today are in English, but that hasn’t always been the case. A few hundred years ago, as a member of the European learned community, you would’ve been expected to read and write Latin if you wanted to engage in meaningful discussion with your peers. Once Latin lost its dominance as science’s lingua franca, scientific discourse splintered into local languages. Researchers worried that the loss of a common tongue would slow scientific progress, so by the middle of the 19th century, they had settled on three primary languages - French, English, and German.

Then, to put it mildly, we all got a bit angry with Germany. After WWI, the German language lost its prominence in the scientific world when German scientists were shut out of the new scientific organizations created by researchers from the US, England, France and Belgium. Things went from bad to worse for Deutsch when, in 1933, the German government dismissed one fifth of the nation’s physics faculty and one eighth of its biology professors for cultural and political reasons. Many fled mainland Europe for America and England and adopted the language of their new homelands - English.

Britain’s colonial history and former dominance as a world power and America’s influence politically and culturally have also exerted an enormous influence on English becoming the world’s common language. And though for many of you it may feel natural for English to dominate the linguistic landscape, there are many who disagree with the switch to this global lingua franca.

“His lectures are funny because his English is so bad”

“Academia should be open to everyone. That knowledge should be free for everyone to use and to read. I think it’s good that it’s settling on a particular language”, says Nikolina Kukoc, bachelor’s student, Sustainable Innovation.

“I think English brings the world together,” says Wouter Ligtenberg of the Computer Science and Engineering Department, continuing, “But there are sometimes problems. I have one teacher and, in Dutch, he’s a really wonderful instructor. But his English is really bad and the quality of his lecture suffers. They’re even funny because the English is so bad and that’s not a good thing.”

The above quote illustrates one of the biggest frustrations for some academics who argue that a lack of fluency in English gives them a sort of “second class citizen” status regardless of their other intellectual abilities. According to the article, The Rise of English: The Language of Globalization in China and the European Union, author Anne Johnson summarizes the debate as such, “Should ability in a language (which is native to some, and to which educational access for the rest is unevenly spread) count for more than one’s field-related expertise? Those who reply to this question in the negative accuse English-only systems of violating the equality of opportunity, and many believe that lingual and cultural rights, like other human rights, should not be left to market forces but instead be protected.”

Professor of Applied Physics, Erwin Kessels, argues that while English is necessary at higher levels of scholarship, a student’s first foray into academic life is best done in his or her mother tongue, “I’m not against teaching in English if there are foreign students in a class but I think that we should be mostly teaching in Dutch at the bachelor level. Most of the students are Dutch and they’re coming to us straight from high school. They haven’t learned how to speak eloquently in Dutch yet. They need to learn to speak well if they’re going to become Dutch scientists. You learn a lot of other skills at university than just what you’re studying.”

The major obstacle for improving English is the fear of making mistakes

Regardless of the debate, however, for now, English is here to stay. And though you may be fluent, everyone could use a tune up from time to time. As busy academics, gone are the days when you could spend hours honing your abilities, so here are some quick tips for giving your English a boost.

First of all, linguists and language teachers alike agree that there’s no one “best practice” for improving your English. Local English instructor, Roz Burden, explains, “Some people learn more through reading, others seem to get a lot out of making vocabulary lists. I find that adult learners often face one major obstacle for improving their English and that’s their fear of making mistakes. They don’t want to look stupid so they don’t speak as much as they should. But speaking is crucial to improving. You can’t speak a language without speaking a language.”

Nikolina Kurac (Bachelor of Innovation Sciences) is Croatian but describes herself as bilingual because, “Growing up, I read in English. English books were cheaper than books in Croatian so I bought those. You need to read if you’re going to become really fluent. It makes you more confident because you then have this inner voice that helps you to voice the words.”

Want to quickly build your English vocabulary? According to theories of language acquisition, doing so effectively could all depend on what your mother tongue is. The conventional method of increasing your vocabulary -translation to your own language and memorization- is okay if your mother tongue is closely related to English, like Dutch or German. But for languages not closely linked (Chinese, for instance) the learning process becomes more efficient when the translation step is removed and the new words are directly linked to actual objects and actions. For example, during dinner with a native English speaker (or someone more advanced than you) they would help you identify different food items, objects and verbs related to eating.

Roz Burden offers yet another method: “Another way to build your vocabulary is by grouping things that are conceptually related and practicing them at the same time. For example, naming things and events related to transportation when you travel to another city or learning all of the terminology connected with a favorite sport.”

Lastly, don’t forget to take advantage of TU/e’s resources. The university’s Center for Languages and Intercultural Communication provides classes for students and staff in English and Dutch, offers courses in intercultural communication, has a translation desk and administers language tests.

Prof. Erwin Kessels offers some final advice for students as they advance through academia and enter an increasingly English-speaking work world: “Not everyone will speak perfect English but you will have to figure out how to handle that. This will be a part of your professional life. When you go out into the real world, you’ll quickly learn that you will have to try a little bit harder to understand someone.”

Discussion