Better 3D-printed heart and kidney tissue with new technique

TU/e researchers have taken a promising step in the development of biomedical materials and 3D tissue for regenerative medicine. Two scientists involved, Miguel Dias Castilho and Lena Stoecker, adapted an innovative 3D printing technique for biomedical purposes. In this way, they hope to create cell-friendly environments that support and guide human cell growth in a more natural way, a possible starting point for more realistic disease models.

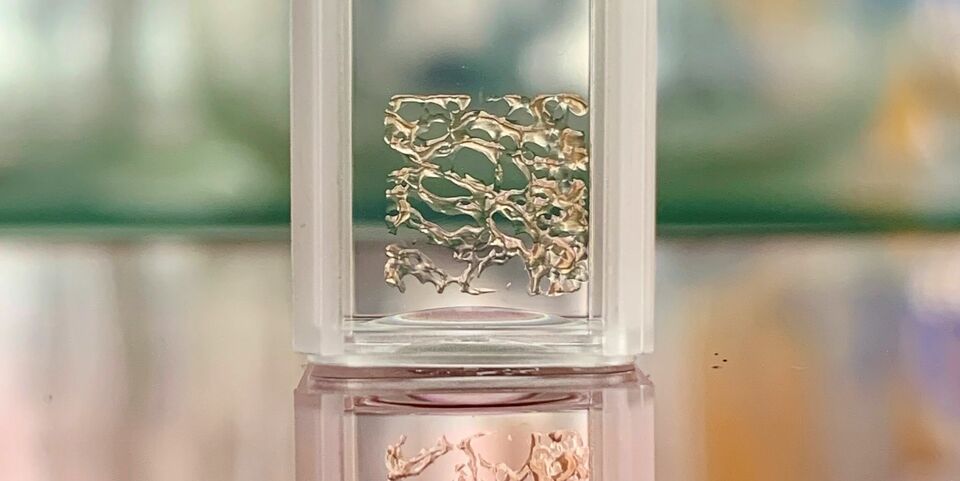

Whereas this method was first used for making jewelry and high-tech lenses, they are now the first group in the world to utilize it to modify the shape and elasticity of special biocompatible hydrogels. And combined with the rapid, high-resolution printing process, that is a potential breakthrough within regenerative medicine.

Because human tissues and organs are very complex and certainly not homogeneous, stresses Lena Stoecker. As a PhD-student, she is working in the new BME-research group Biomaterial Engineering & Biofabrication to develop realistic artificial tissues. "Looking at the bone marrow, for example, we find different cell populations in regions of different elasticity. And we know that biophysical cues such as elasticity but also geometry have an effect on cell behavior. Although a lot is going on in the field of tissue engineering, we largely rely on biomaterials that sustain long-term cell survival but are only two dimensional or have homogeneous properties”

This makes it difficult to realistically mimic the complex structure of functional tissues, such as heart or kidney, says group leader Miguel Dias Castilho. "We have now developed a method in our lab that allows us to print 3D biomaterial constructs with controlled spatial patterning of geometry and mechanical properties for advanced control of cell fate."

Ultrafast printing

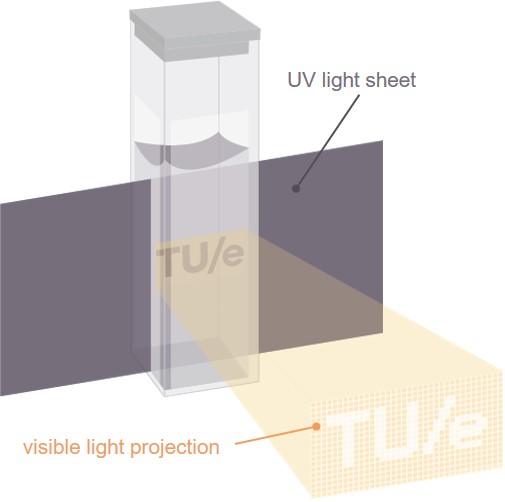

The method developed by Stoecker and Dias Castilho is based on the relatively new 3D printing technique xolography. Using two beams of light of different wavelengths, it allows for the controlled conversion of a liquid material into a solid form. Thanks to TU/e researchers, who employed a suitable chemical formula, this technique now allows them to print three-dimensional structures to grow human cells in. Moreover, by adjusting the intensity of the light beam, they discovered that the elasticity of the 3D structure can be adjusted at specific locations if required.

Printing a biocompatible 3D structure is lightning fast; Dias Castilho can “make a print the size of a gummy bear within a minute.” And with high resolution, Stoecker adds. "We can create adaptable structures the size of a human cell, about 20 micrometers. And we can insert multiple regions with different, dynamic elasticity. This unique combination in 3D is only possible with this specific technology for now."

Heart damage

In the future, they also hope to use this to contribute to new, realistic disease models, for example for research into heart damage, Dias Castilho explains. "After a heart attack, you see that the tissue at the affected site is stiffer than the surrounding healthy heart tissue. We can mimic that more realistically with our programmable print structure. We give researchers a new tool to control the microenvironment of cultured cells in detail, with promising possibilities within tissue engineering and regenerative medicine."

Discussion