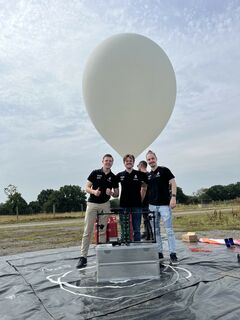

Aster tests first satellite in “near-space”

Recently, student team Aster used a weather balloon to launch a satellite into the sky for the first time. The prototype reached an altitude of about 35 kilometers and eventually landed in someone’s backyard. The purpose of the mission was to determine whether the satellite, including its payload, would be able to withstand the harsh conditions of space.

Bringing Eindhoven closer to space: the launch of a self-built satellite recently brought student team Aster one step closer to that goal. The prototype, which was lifted up into the sky attached to a weather balloon, reached an altitude of 34.8 kilometers. This means it did not actually reach space; that would have required an actual rocket. Nevertheless, the image of the satellite high above the Earth (see main photo) made a big impression on team manager Fares Abuelhassan. “When I saw the photo, all I could do was stare. I could hardly believe it. All of our hard work came together in that one image.”

It was the intention for the prototype not to actually reach space and to return to Earth. This is because the goal of the mission – named “Hydrogen” due to the hydrogen in the weather balloon – was to see if the satellite could withstand the harsh conditions of space. The elongated box is now safely back in the student team’s room in innoSpace, allowing the team members to closely examine how foolproof the prototype is. As it turns out, it is quite sturdy: after a 250-kilometer journey and a landing in the backyard of some very surprised Englishmen, the prototype has remained virtually unscathed – apart from a small chipped corner and a crack in one of the solar panels.

Photonics

Through the mission, the students not only tested whether their own satellite would survive a trip into space, but also equipment from PhotonFirst. “That company specializes in photonics. That technology has not yet been used in space,” says Abuelhassan. “They have a device with all sorts of fiber optic cables and if you wire those in the satellite in a specific way, it can measure several things at once, such as temperature, pressure and radiation.”

By sending that device along with the satellite, the students were able to validate the technology, which, as it turned out, was quite capable of withstanding temperatures of -70°C, just like the satellite itself. The measurements also proved to be accurate, says technical lead Tijn Quinten Zeelenberg. “In addition to PhotonFirst’s equipment, we had a conventional system on board that made the same measurements, allowing us to compare the results.”

No plug-and-play

In future missions, the payload will likely come from external parties as well. “That’s normal with this type of satellite,” says Zeelenberg. “We, in turn, ensure that the satellite works, that we can communicate with it and that the power supply works properly.” It is a platform where something can be integrated, Abuelhassan adds. “That’s not a simple matter of plug-and-play. You have to think about how to do the wiring and how to process the data, for example.”

Now that the prototype has successfully completed its journey, it is time for the next step. Aster is going to build another satellite, one that will be launched into space by a rocket and stay in orbit forever. That last part is what makes it so exciting, because once it is up there, no more changes can be made to it. “All you can do is apply a few software patches,” says Abuelhassan. “So you really need to have confidence in what you’re sending into space. And make sure it was tested properly.” That goal was achieved with mission Hydrogen, and according to Zeelenberg, that brings the team much closer to building the real satellite. “I hope I’m still with Aster when that becomes a reality.”

Eindhoven

There is growing interest in space exploration in the region, the members of Aster have noticed. “There’s momentum for it in Eindhoven,” says Abuelhassan. “Last year, the ScyLight conference was hosted here. Many people from the university participated. And Electrical Engineering, for example, is working on optical communication.” According to the student, Eindhoven has a lot of knowledge that can be useful for space exploration, for example in the field of photonics. “In the end, a satellite is just a computer. Its components just need to be able to withstand the conditions in space.”

To keep the interest in space exploration alive in Eindhoven, Aster, in collaboration with Studium Generale, is organizing the lecture “A Dutch Space Odyssey” with Joost Carpay of the Netherlands Space Office. The lecture is free to attend on Wednesday, October 2 at 12:40 PM in the Blauwe Zaal.

Discussion