Rathenau: ‘Current science policy due for revision’

The Rathenau Instituut has mapped out four developments that impact the future of science. These trends mean current science policy needs to be revised in order for it to remain futureproof. The report Kennis van de toekomst (Knowledge of the future) gives an overview of current obstacles and provides recommendations for creating new policy.

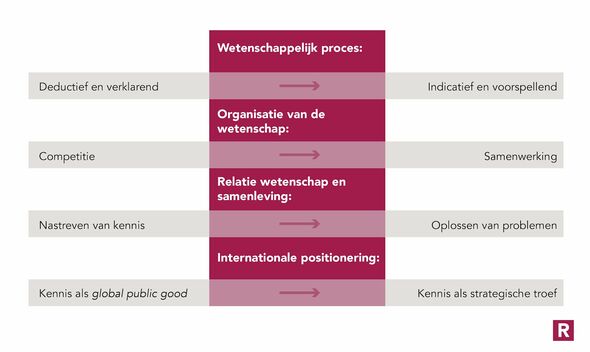

Digitization, climate change, and geopolitical tensions influence scientific practice and how society looks at science. This creates the need for new policy instruments, says the Rathenau Instituut in a new report, which addresses four important points:

- Ongoing digitization and AI

- Stronger focus on coordination and collaboration when organizing science

- Increasing urgency of societal challenges

- Changing international relationships

AI and digitization

When it comes to digitization, the institute says new technologies are making scientific research faster and more efficient. Not only is the availability of data greater than ever before, but this data can also be processed faster using algorithms. The use of AI does, however, raise questions about the replicability and trustworthiness of research results.

In addition, science has become dependent on large tech companies with their essential ICT products. This necessitates a reconsideration of the relationship between the public and private sectors in the area of knowledge development, the institute argues. After all, science must continue to safeguard its independent and public function, but can no longer do without these tech giants.

Competition and collaboration

Over the past decades, striving for excellence has taken up an increasingly important place in science. This gave rise to ‘hypercompetition’; scientists and knowledge institutions compete for money and other means, with the best and most groundbreaking idea coming out on top. As a result, current policy is mainly focused on developing this kind of knowledge and not so much on application-oriented solutions for societal problems.

This has led to the replication crisis: researchers experience a huge pressure to report positive empirical findings, as insignificant correlations are published much less frequently in scientific journals. Multiple studies show that previously published research isn’t replicable, nor of sufficient quality. This isn’t only damaging to science, but as a consequence of this competition less attention is also paid to other tasks of universities, such as sharing and utilizing knowledge to solve societal problems.

The research institute does see an improvement in this area in recent years, but emphasizes it’s still important to think about how scientific collaborations can be organized better and focused less on competition and research funds.

Societal challenges

The dominant opinion within society is that science must provide solutions to the major problems of our time, such as climate change and economic inequality. As a result, an increasing amount of attention is being paid to these subjects in science. The societal impact of research, for example, is on par with scientific impact when it comes to the assessment of funding applications. Initiatives have also been launched to bring scientists closer to society, such as city labs and academic workshops.

According to the institute, it’s important for those devising scientific policy to keep thinking about what society can actually expect from public knowledge institutions, and about how the independence of science can continue to be guaranteed in this respect, especially in case of research involving political interests.

International relationships

Due to geopolitical tensions, scientific knowledge serves the public interest to a lesser degree. The balance of power is shifting on the world stage – one example being the growing power of China – and this is increasing the attention being paid to knowledge security. As a result, scientific knowledge is transitioning from a ‘shared commodity’ to a ‘strategic asset to be protected’. According to the researchers, this calls for reflection: what knowledge should we keep close to our chest from a strategic point of view and who are trustworthy partners?

A new equilibrium

“Now, the question is what new instruments are needed to adapt scientific policy to the changing world of science,” says researcher Paul Diederen in a press release on the report. “It’s important to start the open dialogue about the future of science today.”

Essentially, this calls for a new equilibrium: between the role of public institutions and private organizations, between competition and collaboration, between research for knowledge acquisition and research for urgent societal problems, between openness and knowledge security, and between conducting research for the sake of science and research for the sake of and in collaboration with society.

Discussion