In search of the perfect marathon

TU/e played its part in sporting terms this weekend in marathon land: Juan Restrepo Villamizar, PhD candidate at the Department of Industrial Design, developed a sticker that changes color when your heart rate is too high, or tells you that you’re running too fast or too slow. He tested his ‘smart patch’ during the Marathon Eindhoven this weekend. Professor Bert Blocken at the Department of the Built Environment contributed to Eliud Kipchoge’s record braking marathon in Vienna on Saturday, October the 12th. The Kenyan long-distance runner became the first athlete to run a marathon in under two hours. Blocken conducted wind tunnel tests and used computer simulations to make this achievement possible.

His sticker makes people better understand how to follow their intuition while running, Juan Restrepo Villamizar explains. He tested his ‘smart patch’ for the first time during the Marathon Eindhoven this weekend. It was an exciting day in any event, because this was his first time running a marathon. “The material we have at our disposal so far is a prototype and hasn’t been approved for use with a larger group,” the PhD candidate explains. This is because it’s standard policy at TU/e that researchers follow ethical standards and protect collected data. It is for this reason that Villamizar is the only person to test the ‘patch.’

Eventually, he wants to measure several different parameters: heart rate, running rhythm, body temperate. As yet, the patch only provides feedback on heart rate. The runners have a sensor applied to their chest that sends information via a wireless connection. This is done with a controller. “This way, we provide the runners with feedback in a natural way, without having to look at a screen first.” When the heart rate is too high, the patch changes color. That is the only information is gives, for now. By scanning the patch with your smartwatch or phone after a race of training session, you can read your average heart rate and see what the peaks looked like.

Design of the patch

Restrepo Villamizar explains that the patch is composed of several parts. Applied directly on the skin is a thin layer of foil. “Doctors use it when someone has to stay in bed for a very long time to prevent bedsores.” Then, there is a layer of cotton with an ink on it that reacts to fluids, temperature or electricity. This layer makes it possible to visualize changes in, for example, body temperature or muscle strain. A third and final layer, made from the same material as the first one, holds the device together.

The patch is applied to the forearm. Restrepo Villamizar thinks it will be possible in the long term to apply the patch to the knee and provide information about stress on a runner’s knees. “It doesn’t necessarily have to be placed on the knee, but psychologically, that’s what works best because a direct link is made between the knee and the possible injury.” That is the next step: testing whether the feedback changes the behavior of runners. Should this first technical test prove successful, he intends to add more parameters. This first version is a single-use sticker.

Marathon record

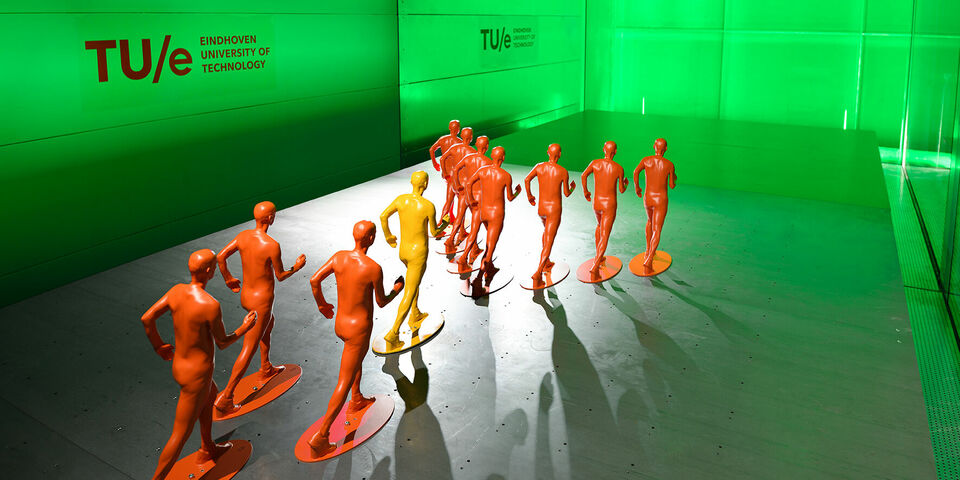

With wind tunnel tests and computer simulations Professor Bert Blocken delivered a substantial contribution to the successful attempt to break the world record on the marathon by the Kenyan athlete Eliud Kipchoge. On Saturday the 12th of October in Vienna Kipchoge became the first person to ever complete a marathon within two hours in the so-called INEOS 1:59 Challenge.The Olympic champion and world record holder for the marathon stopped the clock after 1 hours, 59 minutes and 40 seconds. The record attempt was completed under the best possible conditions. Part of this was a special arrangement of runners, who surrounded Kipchoge in order to lower the air resistance as much as possible. The superior performance of this formation was based on research professor Bert Blocken.

Kipchoge already tried this in May 2017 at the Formula 1 circuit in Monza, Italy. His time of two hours and 25 seconds was impressive, but just above the magical limit. Saturday, at the Prater Hauptallee in Vienna, he was successful. This was partly thanks to extensive aerodynamic research conducted at TU Eindhoven.

In long-distance running, aerodynamics plays an important role. The so-called ‘rabbits’ not only serve as pacemakers but also keep the favorites out of the wind. A single rabbit can reduce the air resistance on the second runner by 50 percent. The formation in which these rabbits run determines the total reduction in air resistance that can be achieved.

At the previous record attempt in Monza, the rabbits ran in a triangle in front of the athlete, reducing air resistance by an estimated 70 percent. To further reduce this, more than a hundred formations were analyzed using computer simulations by aerodynamics specialist Robby Ketchell of AvantCourse (USA) and later by TU/e and KU Leuven researcher Bert Blocken. The most optimal formations from this analysis were then tested in the wind tunnel of TU Eindhoven.

Flow resistance

Against everyone’s expectations, the formation of a reversed V with seven rabbits in front of the athlete and three behind him, proposed by Robby Ketchell, turned out to be the most optimal variant. This reduced Kipoche’s air resistance on paper by 85 percent compared to a runner without rabbits. Blocken: “Two sets of independently-performed computer simulations and the wind tunnel tests all clearly showed this formation to be the best. That was necessary in order to convince the runners of this arrangement.”

The formation may seem counter-intuitive, but according to Blocken, the explanation is logical. “The rabbits have to endure a higher air resistance due to the flow resistance of the funnel, which keeps the athlete Kipchoge out of the wind. In cycling, typically a triangle formation is used at the head of the peloton. This is a good formation when you want to minimize the air resistance for everyone in the group as much as possible. However, for this marathon record, it is only about minimizing the air resistance for Eliud Kipchoge, not for the rabbit. Then this reserved V is superior.”

In addition to the formation of the rabbits, the researchers looked at the distance between the rabbits themselves and between the rabbits and the athlete. The effect of a cyclist next to the athlete (who provided him with food and drink) was also tested in the wind tunnel, as was the effect of a car driving in front of the rabbits with a large clock showing the running times.

Discussion