‘Figure it out:’ practical lessons in Applied Physics

Cooperate, discuss, experiment, being resourceful. The personal skills of second-year Applied Physics students are put to the test during practical lessons in control theory. But ‘cheating’ is allowed. “What counts is the total performance,” says dean Gerrit Kroesen.

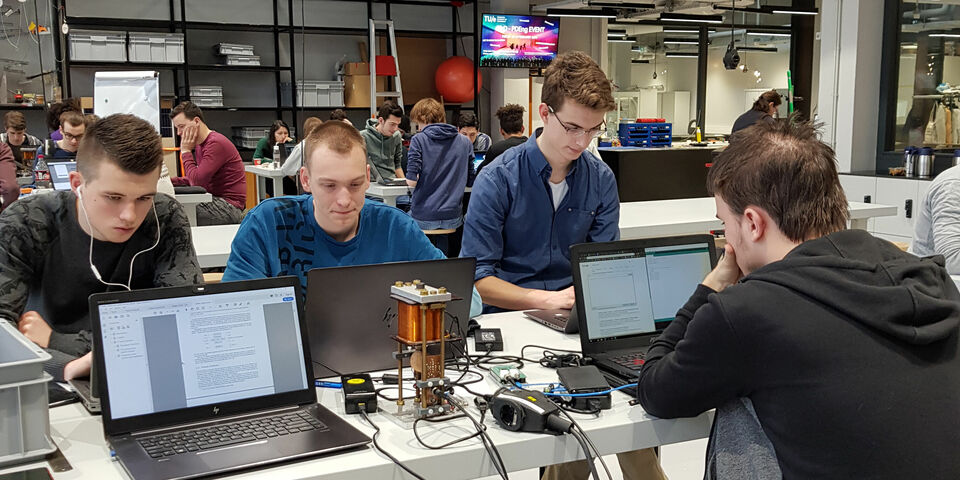

The Department of Applied Physics is literally putting educational innovation into practice. During the next seven weeks, second-year students will try to make a small ball float. Everything they need for this fits in a shoebox. A magnetic coil, a circuit board, some plugs and wires, and a small metal ball of course. The moto is: figure it out.

Simple tinkering? Absolutely not, say dean Gerrit Kroesen and teacher Rudie Kunnen emphatically. Together they supervise a group of 160 students who are working on the assignment. It’s a different educational method. A way of translating theory into practice. “Small-scale, challenge based and hands on” is how Kroesen describes it. “During theoretical lessons students often wait for someone to help them. They raise their hands and stop thinking. Now they have to come up with solutions themselves.”

Kunnen: “We deliberately designed this as an open assignment. There are lecture notes with theory and there is some monitoring in case a group gets stuck. But that hasn’t happened so far.”

Organic

The compulsory practical lessons in control theory are part of Design-Based Learning. “This was a leap into the unknown for us,” Kunnen admits. “There still is a lot of work to be done, but it’s happening fairly organic,” Kroesen adds. They both believe that offering study subjects in a completely different way is a positive thing. Kroesen: “We are a technical program and our ‘clients,’ such as ASML, want people who can put control theory into practice. They are looking for employees who know how to apply systems thinking. That’s logical because one ASML machine has about two hundred control loops.”

Applied Physics has tried practice lessons before. First on a small scale in Flux and once more in the Gaslab. The results of a survey among students were positive. They especially appreciated the freedom they experienced during the lessons, but it turned out that being positioned in rows didn’t encourage deliberation. There was also some hesitation in asking the supervisors for assistance because they were not in the same room as the students. But those problems are now solved with large group tables, a work table for Kroesen and Kunnen, and the space at Innovation Space.

Cheating

Because of the size of the group, the second-year students are divided into two groups of eighty people each. The students learn control theory in practice two mornings a week. They do so in groups of six or seven students. It’s allowed to ‘cheat.’ “You actually learn from that,” says Physics students Rik Heinemans with a smile. “When you get stuck, you can turn to another group to ask them how they handle the problem.”

Heinemans is busy working with his fellow student Chris van der Heijden. He finds that the practical lessons are less attuned to his studies because of the greater focus on theory. “You do learn how to program, as well as other practical skills.”

Hints

What they both like is the freedom that comes with research and experimenting. Van der Heijden: “At a certain moment, we were left with more connectors than connections. When we asked for a splitter we were told that we could do without them. How? Gerrit and Rudi won’t tell. At the most, they give us a hint and let us figure out the rest for ourselves.” The two students have just started with their first practical lesson but they are convinced that their metal ball will float soon.

Sleeves rolled up

The students practice three professional skills: presentation, collaboration and planning. Their assessment follows after a test, a presentation and a peer-review. They supervisors believe that is unlikely that students who perform poorly will profit from the commitment of others. “The students will make sure of that with their peer-review,” says Kunnen.

Even though other deans sometimes consider him mad, Kroesen really enjoys practical lessons, despite his full schedule. ‘With his sleeves rolled up’ he follows the students during four mornings a week. That way he stays connected to the practice of teaching. “Educational innovation isn’t something that only gives you headaches,” he says with a smile.

Discussion