Home Stretch | Surgical robot removes bone

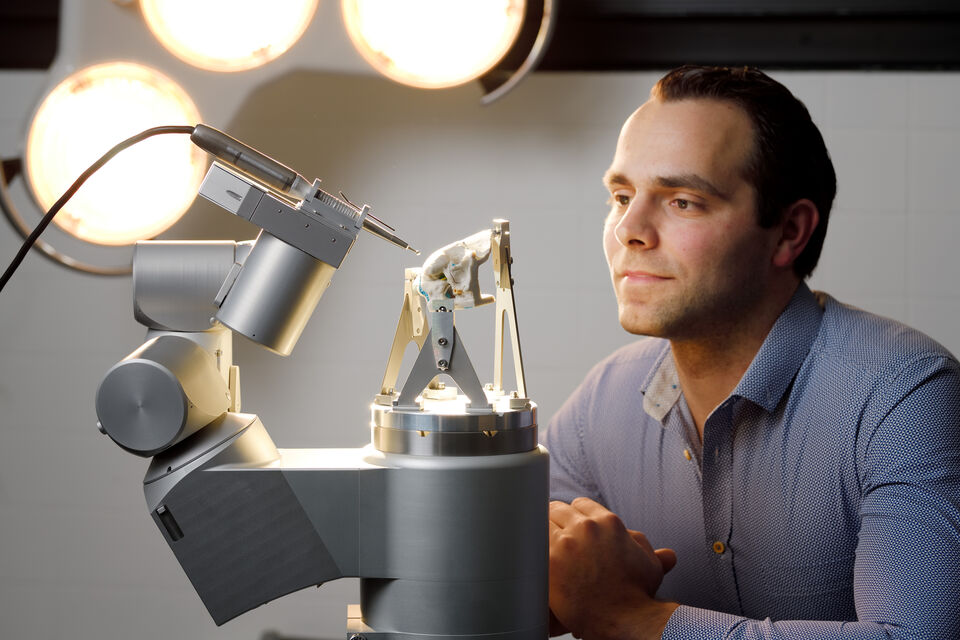

To insert a hearing implant or remove a tumor in the ear canal, the surgeon must remove bone, a specialist job not without risk. This prompted PhD candidate Jordan Bos to design and build a computer-operated surgical robot, RoBoSculpt. Working from a CT scan, it can help the surgeon remove bone faster, more accurately and more safely.

Every year some 65,000 (almost) deaf people worldwide receive what is called a cochlear hearing implant, tells Jordan Bos. “In the Netherlands this group numbers six hundred, but demand is much greater. This is a complex, high-risk procedure that involves removing the bone around the inner ear. In addition, the implant is inserted between two nerves only 2.5 millimeters apart. If this step goes wrong, half the patient's face can become paralyzed. Given the hazards, in the Netherlands this operation is carried out only in teaching hospitals.”

Obscured image

Prior to the procedure a CT scan is made of the patient, so that the surgeon has the best possible image of the vicinity of the inner ear – this is because this region is slightly different in every individual. Even so, during the operation, the surgeon must rely mainly on the image provided there and then by the microscope, which is obscured by blood, fluids and bone shavings. Under these circumstances it is inevitable that more bone is removed than is strictly necessary, explains Bos. “While in principle all that is needed is a tiny hole in the bone through which to insert the implant wire, the surgeon goes in search of the facial nerves in order to avoid nicking them accidentally.”

It would be better to translate the information from the CT scan directly into an operation plan, the mechanical engineer thought. So he developed a surgical robot, a mechanical hand of sorts in which the surgical cutters are clamped, that carries out the operation guided entirely by computer programming informed by the CT scan. “In principle the surgery is based on a plan that is calculated automatically and, of course, assessed and approved by the surgeon. During the operation itself, the surgeon need only observe, checking that everything goes smoothly. If need be, we could build in the need for the surgeon to give the robot permission to proceed after every little step.”

Milling machine

In a sense, his surgical robot, the RoBoSculpt, is a kind of computer-operated milling machine. These are already in general use for the processing of materials, says Bos, and are sufficiently accurate. “But they aren't the kind of equipment that fits into an operating room. Moreover, the materials being processed are often passed under the cutter. That's not something you want to be doing with a patient.”

The RoBoSculpt, by contrast, measures less than 20 centimeters, and with its seven axes of movement can make all the necessary maneuvers while the patient's head is fixed to the operating table. Naturally, Bos has also incorporated the necessary safety mechanisms: “For each of the seven degrees of freedom, there are for example two encoders that measure the absolute position. If the power supply fails, afterwards you can ascertain exactly where you got to.”

Spin-off

The RoBoSculpt has been designed with operations in the vicinity of the ear canal in mind, but it has much wider application. “I think that we can also use the robot in operations where bone must be removed with precision."

The milling robot is not yet fully functional, but the first preclinical tests, as they are called – on pieces of skull belonging to people who have donated their bodies to science – are scheduled for later this year. Subsequently, with the new spin-off company Eindhoven Medical Robotics, it should be possible to launch Bos's invention commercially within four years. “We expect RoBoSculpt to open the way to carrying out this operation outside of teaching hospitals, which will make it possible to help more patients.”

Photo | Bart van Overbeeke

Discussion