This is not an exit

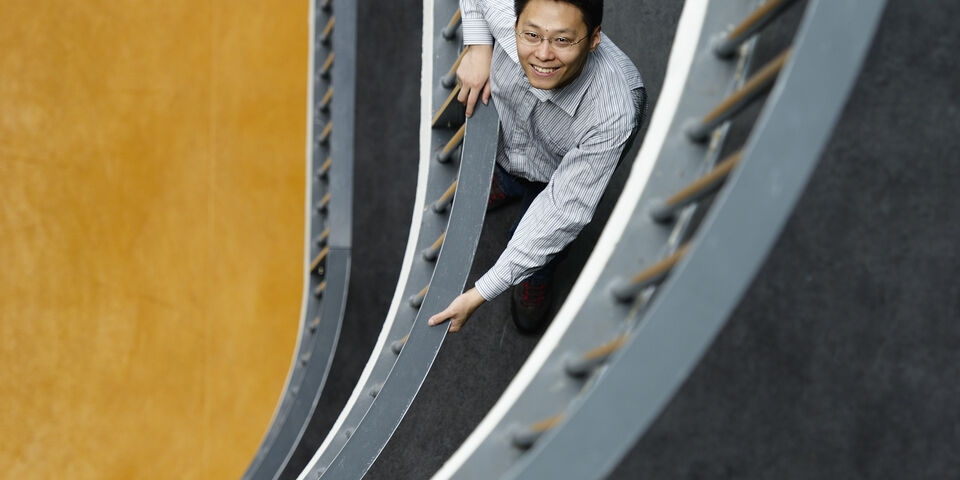

In some buildings it’s easier to find your way than in others, and that’s not just a matter of following signs. The architectural structure of a building -how hallways and doors connect spaces- plays an important part in this, especially in stressful situations. Next week, Qunli Chen from China will receive his doctorate degree at Design Systems of the Department of Built Environment for his dissertation on the subject.

You’re nervous and running late for an interview. Or worse: the fire alarm is sounding and this time it’s not a drill. Because of the smoke it’s hard to read the signs pointing to the nearest fire exit. You haven’t been to this office very often and haven’t been able to familiarize yourself with its floor plan. While passing through hallways and opening doors, you’re relying on your intuition mostly: take the first door on your right, then that wide corridor on the other side of the room, and then it’s hoping the architect thought to connect the offices in a way that makes sense.

Well, very often they didn’t, says Qunli Chen. “Architects want to create a building with a unique identity, often at the expense of logic. They forget people expect a certain structure: a door usually opens up to an enclosed office space, but a hallway tends to lead somewhere.”

As an example, Chen mentions Vertigo, the buildings he’s been frequenting the past four years. “Stepping out of the elevator, you see two identical doors – one to your left, one to your right. There’s no floor plan in sight and there’s no way of knowing the door on the right leads to the department’s reception; that can only be deduced from the signs, which you only notice upon closer inspection. However, looking straight ahead you do see the toilets and the staircase. It’s pretty weird to me, to be honest.”

The consequences of being late to an interview, let alone those of a fire, can be bad enough in their own right. You’d think some basic knowledge about people’s expectations of the layout of a building is important, then. Still, Chen found out that in the past, people have been researching signposting mostly: where should signs be located, what size should they be and what color works best? “The architectural structure of a building is often considered a given, although studies show rushed people have trouble locating these signposts and are guided by architectural pointers just as well.”

It was a reason for Chen to set up a number of meticulous experiments to test whether people’s navigational behavior in (relatively) unknown buildings can be captured in fixed patterns. Do they often go for the first door on the right, or rather opt for the widest hallway they see? “We were looking for results that have nothing to do with cultural background. Reactions to certain colors can be highly culturally-dependant, for example. Mailboxes in the Netherlands are orange, but in China, they’re blue. Orange will have a positive connotation for many Dutch people, but not for Chinese, who will feel that way about red and gold. For that reason I decided to create simulations using grey tones, distinguishing between light and dark only.”

The doctoral candidate of Built Environment designed a fictitious office building with eighteen connected rooms. Each room has two or three doors or hallways leading to another room. Subjects were asked to navigate through the office building like it was some sort of computer game. Goal of the experiments was to predict, given a certain configuration, the possibility a subject would choose a certain exit. Architects should take that information into account in their designing process.

The Chinese doctoral candidate used different angles, distances and width as well as variations in background contrast for the various exits from each room, and analyzed the effects these variations had on the subjects’ decisions. Subjects were given assignments such as: you’re on your way to an interview and are looking for the room you need to be. You’re running late, so you have to make quick decisions.

Being pressed for time is important: although Chen doesn’t deny the benefit of fire drills in the Netherlands, he does have an issue with them. “Last year I participated in a fire drill myself, but everyone was extremely relaxed. If pressured, people make other decisions, so drills like that are not representative.”

In another experiment, each subject was allowed to repeat the exercise three times. “That’s enough to get an idea of the building, but not enough to create a mental map of the way all areas are connected. There’s still a high level of intuition involved.” Still, subjects were faster at reaching their destination the second and third time around.

“One thing that should always be taken into account is that people tend to notice things that are within forty degrees of their line of vision.” Another thing that clearly shows from the experiments is that women are more likely to opt for lighter and wider hallways. “Although some female subjects were a bit more adventurous and chose darker corridors”, Chen laughs.

One of the subjects had served in the army and always chose the first door he saw. Apparently he didn’t want to stay in open spaces. The experiments showed the exit right in front of a subject is generally the most popular. Another common strategy was to pick the first door on the right (or left) every time, which is a good way to find your way out of a maze.

He hasn’t visited the new MetaForum yet, Chen says upon hearing undersigned hasn’t exactly familiarized himself with the building yet. “From what you’re telling me I gather the building relies heavily on its signposting. And if those signs are not up yet, that’s a problem. And another thing: signs always seem to be put up in dark corners. Paying attention to details like that professionally never ceases to amaze.”

Discussion