Home Stretch | On fire

Mechanical engineer Niek van Rooij developed iron powder boilers for factory use

It works in the lab: iron powder as a renewable energy source. Combustion releases a lot of heat and no CO2, and the residual products can be recycled into new iron powder. But TU/e PhD candidate Niek van Rooij, thinking beyond the lab setup, investigated how iron powder fuel can become commercially viable. On Friday, February 28, he will defend his dissertation – or dissertation design as he prefers to call it himself – at the Department of Mechanical Engineering.

Niek van Rooij is a practical guy. In no time he was happily driving around in a forklift truck on the premises of Swinkels Brewery, he says with a sparkle in his eye. Four years ago, he got his hands on the first scaled-up pilot installation – a collaboration of TU/e, Emgroup BV, Heat Power, Romico, Team Solid, and Metalot – that can produce heat using iron as a fuel. To gain more insight into the iron combustion process on a larger scale, he modified the setup with various measuring instruments. The entire system was placed on the brewer’s property. A challenging test case to take iron powder out of the lab and use it in making factory processes more sustainable.

Rust bucket

Iron powder is definitely sustainable, Van Rooij explains enthusiastically. “In theory, you can reuse it infinitely. When you burn iron powder it produces a lot of heat, and iron oxide – rust – as a residual product. You can bring that back to its original state, iron, in a reaction with hydrogen.” He compares it to a battery. “In combustion, energy is released, and you’re left with an empty battery, basically a rust bucket. You can convert that back into iron powder, so your battery is charged again. And if you use green hydrogen in that conversion, you have a very clean process.”

Iron powder offers many advantages as a fuel, Van Rooij says. “You can store a relatively large amount of energy in it, its combustion is CO2 free, and the fuel is circular. Moreover, iron is not a scarce resource, and it is relatively easy to store.” Although a great deal of fundamental knowledge about iron powder fuel has been gained in recent years, the step toward industrial applications is missing. And that step, says Van Rooij, must now be taken. “We’ve made a start, in a process involving a lot of practical tests, trial and error, and measurements.”

Hard cake

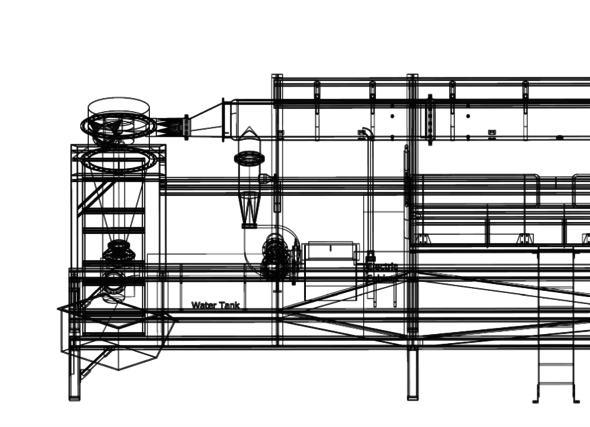

The sheer scale of it is already quite daunting. Van Rooij shows a picture of a hefty installation, about 8 meters high. It’s no wonder this works differently than an arrangement on the lab table: “Everything is more awkward and slower.” In addition, there are many practical problems. One of the biggest challenges is how to recover as much iron as possible from the process. “In the combustion reaction, the iron powder melts, but you want to prevent it from sticking to everything in its molten form. After all, when it solidifies it becomes a hard cake and you’ve lost usable iron. But to heat water with the released heat, you do need a boiler with walls.”

By experimenting with the flame in the combustion chamber, which is supposed to ignite a mixture of oxygen and iron powder, that recovery of iron “worked out pretty well,” Van Rooij says. “We showed that it’s more advantageous to have the flame burn in the same direction as gravity, from top to bottom. Normally a flame burns the opposite way; just look at a lit candle. And you have to give the flame plenty of room on all sides.” Another important trick is letting the iron oxide particles cool down before they come into contact with a surface. How to do so? In a nutshell, it’s all about giving the particles ‘sufficient time’ to cool down, and keeping the contact surfaces ‘cold’. But what exactly do ‘sufficient time’ and ‘cold’ mean in such a complex process? Van Rooij winks: “That’s the secret recipe.”

Coarse iron powder

The particles that were successfully captured could then be studied in detail by Van Rooij, giving him a lot of information about the combustion process. “Ultimately, you want as much of the iron powder as possible to be converted into iron oxide. But how does iron react with oxygen on such a large scale? With electron microscopy, particle size analysis, and oxygen analysis, we were able to analyze the powder and determine optimal conditions for efficient combustion. Again, it was a lot of tweaking and testing.” So can’t such experiments be captured in a model? They certainly tried to do so, he stresses. But because it is such a complex and new process, there are no accurate models yet, so they didn’t get any further than a simplified model. Which is, quite simply, less useful than a real installation.

All the experimental work certainly constitutes some big steps, says Van Rooij. “We were able to modify the design so that we can now also burn coarser iron powder much more efficiently. We used to work only with very fine powders. Those burn great, but are much more expensive. A big disadvantage for industrial applications. The fact that we can now achieve similar combustion efficiency with a cheaper raw material offers perspective.”

Investing in the ecosystem

In addition to the 100 kW demo plant running for 30 minutes in 2020, a modified second design came into being in 2023 – thanks to Van Rooij’s many tests. This 500 kW system generated heat for 9 hours at the Swinkels Brewery site. And TU/e spin-off RIFT is working on expanding the system even further. “A promising progress,” Van Rooij says. But he’s also realistic. “It’s very nice that we can scale up from a combustion point of view, but as long as we can’t charge optimally and we don’t have a good ecosystem, we’re not there yet. It’s very nice that it works in the lab, but how do you convert giant heaps of rust back to iron? Where do we get clean hydrogen from? We need to make the process circular. A good next step would be to scale up the reduction part, which is already in the works. Fundamentally, we already have a lot of knowledge about iron powder fuel. And we can use that science to refine the technology.” But, concludes Van Rooij – practically minded for a reason – “now we have to crank up the process as a whole and just go for it.”

PhD in the Picture

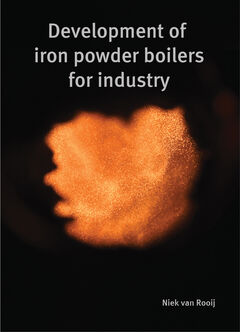

What is that on the cover of your dissertation?

“A look inside the combustion chamber – the image I saw during countless experiments. To make measurements, we placed viewing glasses in the combustion chamber. You can see iron powder burning.”

You’re at a birthday party. How do you explain your research in one sentence?

“How we can make iron powder combustion suitable for industry. In the beginning I got a lot of comments about our research partner Swinkels Brewery, which is of course great for a beer lover. But although we really enjoyed working together, I didn’t get much out of the beer aspect itself. With our technology we supply steam, and how that heat is used afterwards doesn’t really concern us.”

How do you blow off steam outside of your research?

He chuckles: “That’s something I did quite literally during my research; we were looking to generate as much steam as possible. Outside of my work, I like to do sports. I spend a lot of time on the spinning bike, and I recently started lifting weights.”

What tip would you have liked to receive as a beginning PhD candidate?

“Don’t get bogged down in a tight schedule, but do set clear goals. As early as high school you’re trained to plan things out, but experimental research is difficult to plan out. It demands a lot of your flexibility: you may be able to foresee ten things, but the number of things you can’t foresee may be tenfold. That’s how you learn to deal with setbacks and delays.”

What is your next step?

“I’m looking around in the business world, preferably for something like project management at a somewhat larger company. And since I’m very much into mountain sports, I hope to combine the two. A new challenge in Austria or Switzerland would be great.”

Discussion