“Exciting things happen where mathematics and art meet"

Tom Verhoeff brings Bridges Conference to Eindhoven

What happens when mathematics meets art? You can find the answer at the Bridges Conference, which is being hosted in Eindhoven for the first time this year. TU/e researcher Tom Verhoeff – who also creates “math art” himself – is bringing the event to campus just before his retirement.

Many forms of art will be featured at the conference, including visual art, poetry, dance and theater. But when does theater, for example, have a clear connection to mathematics? After all, you could argue that nearly every play follows a structure that can be explained mathematically. However, according to Verhoeff, that is not enough: “For a play to be considered at Bridges, the connection to mathematics will have to be made explicit.”

That connection might come from the representation of a mathematical principle in the play, but also from portraying characteristics of mathematicians and the way they interact with each other. “It might even be enough if the play was written by a famous mathematician,” says Verhoeff. According to him, the most important condition is that the creator has a good story to accompany the artwork – one that also makes mathematical sense. That said, there is also room for more indirect connections at the conference, such as the use of mathematics to detect art forgery, Verhoeff adds.

Both mathematics with an artistic angle and art with a mathematical angle are welcome at Bridges. It should be noted, however, that not every visualization of mathematics is automatically considered art. Verhoeff experienced this firsthand several years ago when he reached out to choreographer Roos van Berkel about adapting a mathematical proof into a dance. According to him, she was initially not that interested, because purely visualizing a mathematical concept was not enough for her. “Then, I created visualizations of the proof, with intertwined objects. That’s what eventually won her over.”

The result was Lehmer’s Dance, in which the choreographer and dancers incorporated elements that were not mathematically relevant, but did add artistic value. “The choreographer used the mathematical background of the piece as a starting point, but the details, properties and theorems surrounding the mathematical structure were less important to her. But for me, they were actually at the very heart of the piece.” The conference is a fertile ground for this kind of cross-pollination between mathematician and artist, according to Verhoeff.

The art of mathematics

There are extra-long breaks during the conference to foster such collaboration. Often, there is also a collaborative artwork that participants put together over the course of the conference. To enthuse people from outside the community about the connection between mathematics and art as well, there will be a Family Day, featuring public activities open to everyone. And there will be an exhibition.

Verhoeff has submitted works for the exhibition in previous years, primarily those made by his father, Koos Verhoeff, who was also a mathematical artist. He sees this conference – which he managed to bring to Eindhoven just before his retirement –as an opportunity to bring his father’s work back into the public eye. “Perhaps in the form of a separate exhibition featuring Dutch mathematical artists, including my father and, for example, Rinus Roelofs, who creates the most beautiful things.”

Eindhoven influences

But that is not the only Eindhoven touch to this edition. Verhoeff has received requests from various quarters to pay special tribute to Dick de Bruijn, a former TU/e professor. “When he came to TU/e, he was already a professor in pure mathematics. He made the remarkable shift to applied mathematics, at a university that had yet to make a name for itself. It was quite something.” In Verhoeff’s view, De Bruijn was one of the last universal mathematicians, but what’s more relevant to the conference is that in 1954, he introduced M.C. Escher to the general international public and that he was also interested in the relationship between mathematics and art.

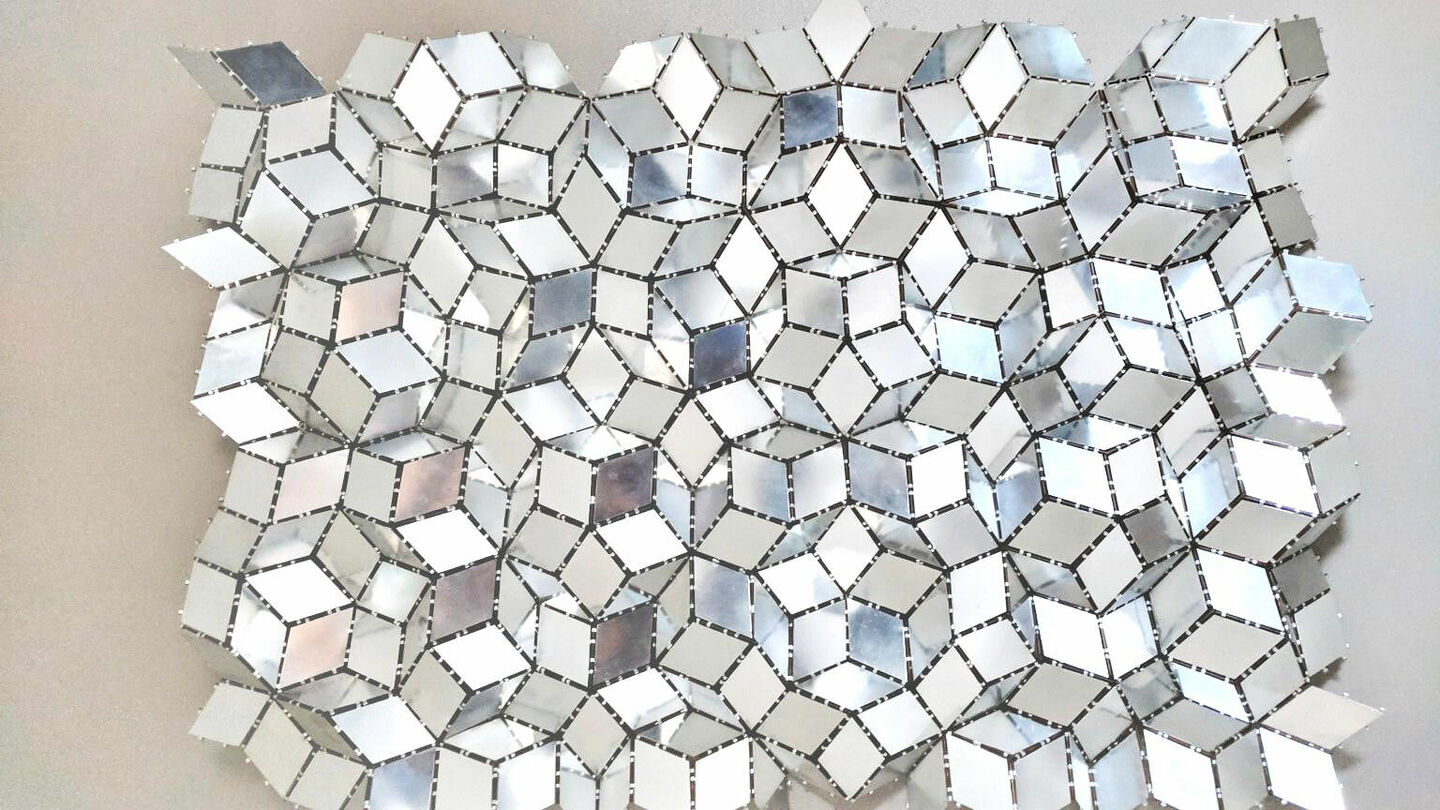

Researching De Bruijn in preparation for the conference has turned him into somewhat of a historian and archaeologist, says Verhoeff. He went in search of works by the professor, including Dak van Wieringa [Wieringa’s Roof], an artwork that used to hang in the former main building (now Atlas). “The roof was named after a student, Rob Wieringa, who came up with the idea. The theory behind it, from De Bruijn, came as a bolt from the blue at the time. It’s so beautiful mathematically. He also worked with Mechanical Engineering to realize the artwork.” Verhoeff managed to trace the artwork and it turned out to have been taken by the student the piece was named after. “I get to borrow it for the conference.”

There will be even more Eindhoven influences during the conference, and who knows, that might also spark some interest from TU/e. Verhoeff: “There’s a risk that art might deter people here somewhat, as it could be seen as too emotional. So it’s possible that no one from the university will show up and everyone will think: whatever, they’re crazy. But that would be unfair. Because I truly believe that it would be quite interesting for people to come and take a look.” For those who can’t wait, all the papers from previous editions are available on the Bridges website.

The Bridges conference is free to attend for students and staff – with registration – on campus from July 14 to 18. The first deadline for the submission of regular papers has already passed, but those who want to submit a short paper or artwork, for example, still have time. All information and deadlines can be found here.

Discussion