US | “Great uncertainty within the academic community”

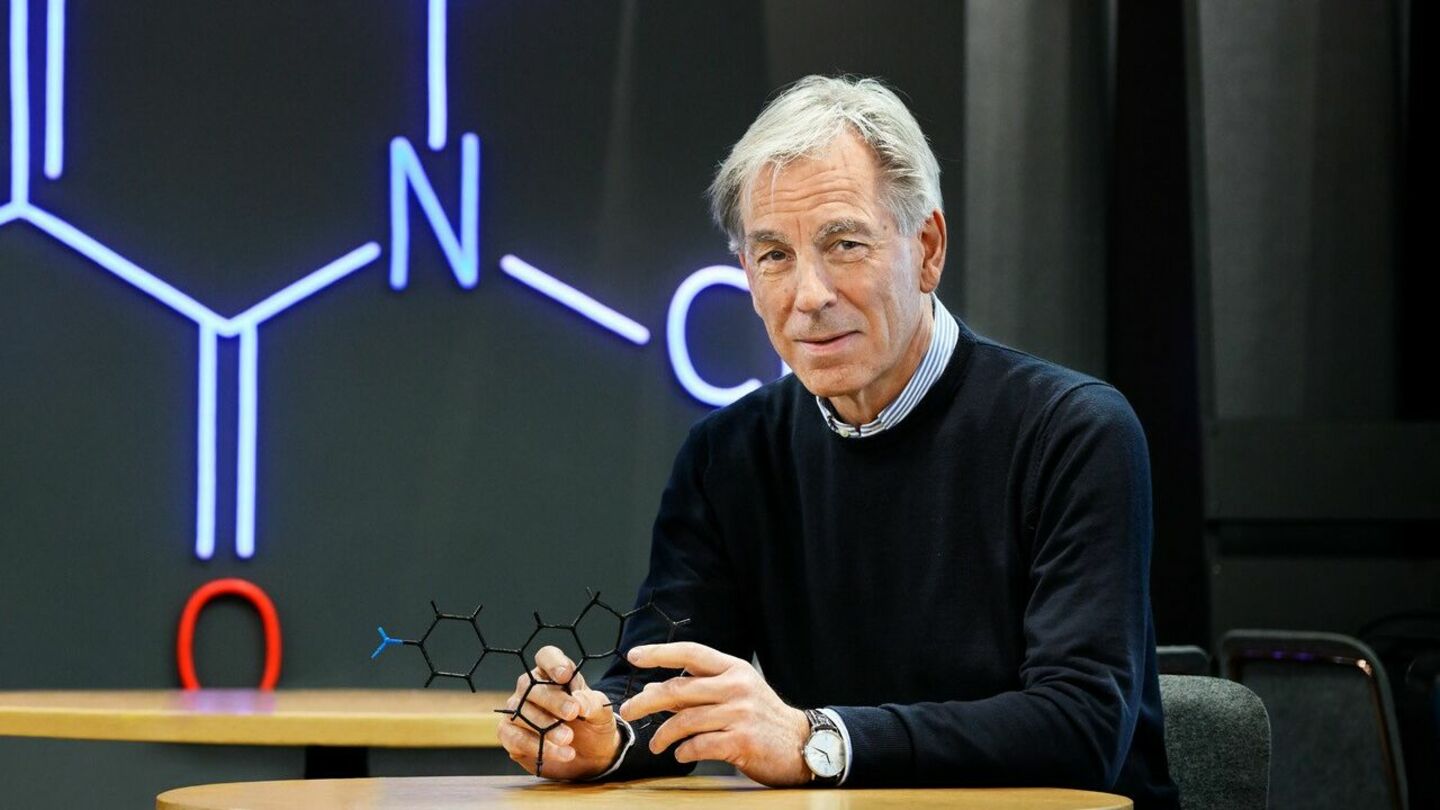

Professor Bert Meijer recently visited the US and saw growing concerns among colleagues there

Discontinued grants, postponed conferences, data gone missing… These are just some of the effects of the new science policy in the United States. What does this mean for education and research at TU/e? And what can we do about it? In this series, members of the TU/e community have their say about the matter. Up this week: Bert Meijer, professor at Chemical Engineering and Chemistry.

It was only a week ago that chemist and full professor Bert Meijer returned from a trip from the United States. He was there to give a number of ‘named lectures’, having been invited to do so by several universities. Some of them were more anxious than others, he noticed on his trip along the East Coast, but there was one common denominator: uncertainty among the academic community is great.

Meijer is connected to America in a number of ways. For one thing, he has held an appointment at the University of California Santa Barbara for more than 20 years, collaborating with the institute extensively. He’s also a member of three academies, including the National Academy of Sciences (NAS). Many NAS members called on the US government to cease its attack on science in an open letter, which Meijer also signed. ‘The voice of science must not be silenced,’ the letter reads.

Are you worried about the Trump administration’s actions when it comes to science?

“On my tour of four universities, I didn’t speak to anyone who isn’t worried – and ashamed – about what’s happening in the US. What makes things very difficult is the uncertainty and the suddenness with which the measures are implemented. American scientists have to bring in much of their funding through grants. They were already writing like crazy to do so. And they were already going through a period with fewer opportunities when the measures hit. That makes it overwhelming. When writing grant proposals, you now have to pay very close attention to whether your intended research aligns with the new thoughts on what you’re actually allowed to do research on.”

“My main concern isn’t science – it has survived many world wars – but a crisis of a much larger scale. If you read historical accounts, it’s like we’re back in the 1930s and we all know how that turned out. Let’s hope we realize sooner than we did back then that we must build a bright future together, not least for our children and grandchildren.”

“What’s happening in the US is also happening here. The Netherlands is also seeing layoffs and study programs being cut. Direct government funding is just about enough to pay the salaries, it’s becoming increasingly difficult to get money from the Dutch Research Council, and I heard that the European Research Council is also getting less. The universities aren’t in good shape.”

Do you personally notice the effects of the measures in your work?

“Not yet. I do have a Chinese postdoc in the group. He had a fellowship to go to America and then it turned out that he wasn’t welcome there because he completed his bachelor’s at a university affiliated to the Chinese military. So then they asked me if he could come here instead.”

“In the US, all of the changes have only been going on for a short time. They’re afraid of what will happen, but aren’t noticing much in concrete terms just yet. What you do see is that there are hiring freezes already, that people aren’t getting the money they were promised, and that you’re no longer allowed to use certain words in grant proposals. Scientists are of course smart enough to adapt. Just the other day, one of them told me that he just uses ChatGPT to make sure that the words that are no longer allowed won’t appear in his proposal. In the end, it’s just words: you can’t write ‘sustainability’, but you can write ‘recycling’.”

What threats do you see for your work, TU/e, and education and research in general?

“My biggest concern is the scientific center of everything shifting to China. They’re making incredible investments in scientific technology there. You already see that half of the papers in top chemical journals come from China. If that country is going to dominate the global economy, you don’t know what’s going to happen. America was sort of like a brother to us, but I don’t know how things will go with China. If we don’t keep investing ourselves, we’ll soon become the world’s museum, as Draghi (former president of the European Central Bank, ed.) wrote in his report.”

Do you also see opportunities?

“At the moment, no. Let’s just stay calm and collected in the Netherlands and not create any further polarization. We should also realize what a luxury position we have. I find it sad that universities are now demonstrating against government cutbacks in education and research. You can’t help but feel embarrassed when you compare that to real issues, such as people not being able to afford breakfast for their kids or find a house to live in. It reminds me of 2020, when the corona pandemic had just hit. Back then, I said in an interview with Cursor: ‘Bearing in mind the idea “never waste a good crisis” I hope that we go back to what is really important in life, and that we care more about each other than about personal success.’ That still holds true today and is actually becoming more and more important.”

What do you think TU/e could or should do to protect its own research and education?

“I don’t think there’s much that TU/e can or should do. We’re a small university and won’t be hugely affected by the measures in the US. We should continue to focus on a clear future plan to address the challenges we have here in the Netherlands. How do we ensure that TU/e has the highest quality of education and research? That’s already quite a challenge given decreasing revenues and declining basic knowledge of incoming students, while technology is becoming more and more complex.”

Discussion