Faas Moonen: ‘I don’t think in terms of doom scenarios’

Farewell to a scatterbrained man of ideas

Faas Moonen is retiring, which means the Department of the Built Environment is losing an innovative spirit, driven by limitless optimism to make sure every project he took on generated attention for sustainability in the building sector. In an interview with Cursor, he looks back at his rich TU/e career: “My biggest pitfall is that I like everything.”

Even if you don’t know Faas Moonen, you probably know ‘his’ GEM Tower: a striking orange and red festival stage with a built-in wind turbine. This originality is a feature of all of the construction engineer’s research projects, as is the focus on design and sustainability.

Moonen himself is a “scatterbrain and true optimist”, who feels at home in the intersection of various disciplines. He’s also very fond of students, who will have to make do without their beloved associate professor from now on: Moonen is taking early retirement. Cursor talked to him, not just about his time as a student and 32-year career at the Department of the Built Environment, but also about concrete rubber ducks and bat accommodations on electricity boxes.

Punch cards

In retrospect, Faas Moonen thinks it says a lot that he graduated on the topic of prestressed wooden building constructions in 1983, back when nobody really cared about sustainability. “I already knew subconsciously that timber construction and other types of sustainable construction were the future.”

Moonen (1958) was born in Budel and raised in Nuenen. As a student, he would ride his bike to a university that looked completely different from now. “The Built Environment didn’t have its own building yet. The first years we were in the Paviljoen (now the location of student towers Castor and Pollux, ed.) and after that in the main building, which is now called Atlas.”

Not a single computer could be found on campus. “Except at the Computer Center, now known as Neuron. There was a device of giant proportions there, with less computing power than my current laptop. We’d write programs for it and entered them on punch cards.”

Telephone

Moonen graduated during the economic crisis of the early 1980s, when unemployment was extremely high. He jumped at the opportunity when Philips offered him a job. The Eindhoven company was making a name for itself in China, and Moonen went there to build industrial sites.

“The Chinese way of building turned out to be very different from the Dutch way, but not wrong. This gave me a very broad perspective: there’s always more than one path to a goal.”

Nine years later, exactly around the time he started wondering if he – now married and father to the eldest of his two children – still wanted to spend eighty percent of his time in China, the phone rang. “It was my old thesis supervisor, Joop van Ploeg. There was a vacancy for a lecturer of timber constructions and he was wondering if I’d be interested.”

Improvisation skills

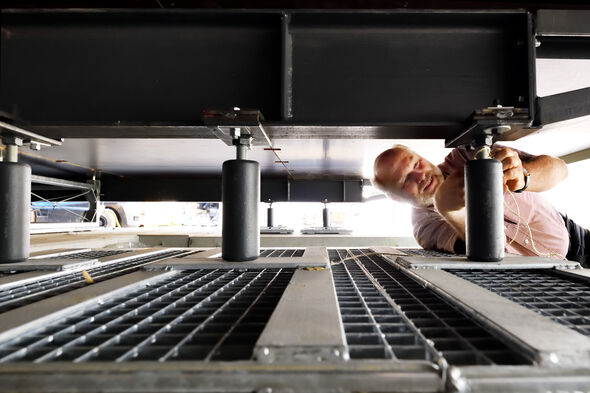

This is how Moonen, in 1992, became a lecturer at his old department, where he obtained his PhD nine years later as well. The PhD research demanded a lot of his improvisation skills, which he luckily possesses in spades: “I developed a new industrial construction system in timber, but the first tests didn’t work out due to a foundation that was off by several centimeters, which meant the construction didn’t fit.”

This required all kinds of alterations on the construction site, taking away the financial advantage of a readymade construction system. Moonen thereupon decided to head into another direction with his research, developing a foundation that could mostly be prepared in the factory, minimizing the chances of unpleasant surprises.

Two students agreed this was an excellent idea and asked Moonen if they could use it as business idea for a course. One thing led to another and they secured a 250,000 euro grant. “The start-up of back then is now a serious company that employs a hundred people and produces a ton of foundation every year.”

Freewheeling

Between 2006 and 2013, Moonen was a program director. Although the position was a great fit for his love for education, it demanded a lot from him. “In that period, we had to come up with an entirely new curriculum, which took a lot of time and energy. After that, I decided that I wanted some room for freewheeling, for doing stuff I like to do. And I did, with great projects crossing my path that I managed to find the right funding for.”

A key moment in all of this was when Moonen met former radio DJ Jan Douwe Kroeske. “He was working on bringing science to festivals and took me on board.” Before Moonen knew what hit him, he was standing in front of an audience of Pukkelpop festival visitors with a container full of concrete rubber ducks.

“I had personally cast the ducks in lightweight concrete, an invention by Theo Salet (professor in Eindhoven and dean of the Department of the Built Environment, ed.).” Thanks to their excitement about the ducks – they’re floating! – the audience was happy to listen to Moonen’s presentation on the technology and applications of the light concrete in housing construction.

100,000 liters of diesel

The GEM Tower, recently developed into the GEM Stage, was also inspired by Moonen’s visits to festivals. He was shocked by all of the aggregates humming away there. “And at festivals branding themselves as sustainable, no less. They were burning 100,000 liters of diesel for three days of partying.”

Together with PDEng candidates Floor van Schie, Patrick Lenaers, and Marius Lazauskas, he developed the GEM Tower: a tower that is easy to move and that generates sustainable energy, using a wind turbine, among other things. Its creative design and bright colors also make the tower an eyecatcher on the festival grounds.

You can’t change the world with one project. But if you manage to garner a lot of attention, you can inspire others, and a flywheel effect is created

The tower was present al all kinds of festivals, and even much more unique locations during the COVID pandemic: “A military encampment, the Zandvoort circuit, and even Soestdijk Palace.” The tower has now been expanded with a stage in the same style, the GEM Stage.

Will the Lowlands festival grounds be full of GEM Stages in a few years’ time, so aggregates will be a thing of the past? No, we’re not quite there yet. “You can’t change the world with one project. But if you manage to garner a lot of attention, you can inspire others, and a flywheel effect is created.” Moonen is happy that this part of his heritage – creating impact with sustainable projects that capture attention – is in the safe hands of Floor van Schie (who’s a university lecturer these days).

Doom scenarios

All of Moonen’s projects are linked to sustainability. Is he worried about the future of the world we live in? “We definitely need to make major changes, but I see opportunities rather than problems. I don’t think in terms of doom scenarios, such as climate plans posing a threat to the economy. I think the opposite is true.”

That positive outlook is characteristic of Moonen – “I’m a true optimist” – and comes in handy in his work. “I think in solutions, which means I generally manage to get all of the parties in the traditionally conservative construction sector on board.” He likes to be a connector, both in practice and in science: “I know enough about the basic principles of building physics, architecture, and construction management to bring together those disciplines.” He prefers not to choose a specific area of expertise: “My biggest pitfall is that I like everything.”

His chaotic nature is a slightly smaller pitfall, and one for which Moonen has made allowances. “I’ve always had support in large projects.” This support was given by colleagues such as Angela Looymans, Monique Sanders, and Monique van Gaalen, “but in some projects also by my daughter Iris Moonen, who followed in my footsteps in terms of study program but is my polar opposite when it comes to being organized.”

Different person

At Moonen’s farewell party in early July, students presented him with a special award. He has always wanted to mean as much to his students as his own teachers meant to him in the past. “The lines of communication between students and teachers are extremely short here in Eindhoven. It used to be that way and nothing’s changed. That close contact is unique, and often very surprising to international students.”

“If you’re a new first-year student, you’re already a different person by the time you go home for Christmas. Not just because you’re living on your own now – which they don’t do as often anymore anyway – but because of the individual responsibility you get here, all of that room to make mistakes.” Together with a student assistant, Moonen once thought up the recruitment slogan ‘Eindhoven builds character’ for the department. “We even had it printed on T-shirts.”

Moonen didn’t only ‘talk’ to his students at lectures, but also at the Bouwkundewinkel, which he has supervised since 2001. “At one time, the university had seven departments with their own science shops (where businesses can ask students for help meeting challenges, ed.), but now the one at Built Environment is the only one left. What saved us was the fact that we successfully made the Bouwkundewinkel part of the curriculum, thereby guaranteeing funding.”

In addition, Moonen stood at the cradle of the VirTUe student team, which was a product of the Smart Cities honors track he developed.

Personalized solutions

Isn’t Moonen afraid the close contact between students and teachers will disappear now that TU/e is getting bigger? “No, that mentality won’t change. Although I do think things are sometimes overregulated. The PER (a department’s program and examination regulations, ed.) used to have less than ten pages, now it has well over a hundred.” As a program director, he would always talk to the student concerned if there were any complaints. “And we’d usually be able to work something out, putting the student’s interests first. I’m sure those personalized solutions will continue to exist, even though finding them might demand a bit more creativity.”

He also doesn’t expect education to change due to the growing student numbers. “Now you can take online classes from leading scientists all over the world, the emphasis is shifting toward processing and applying the knowledge acquired. You can’t learn that digitally. And that’s exactly what we’ve been doing here all along: the Built Environment has already been engaging in challenge-based learning for fifty years.”

Bats

Moonen’s early retirement is the result of the very busy years he has behind him. “Two years ago, our colleague Rijk Blok passed away very suddenly, and I took over a lot of his tasks. In the meantime, a successor for him was appointed, but we are still looking for a full professor for my Sustainable Structural Design group.”

Although Moonen is giving up teaching entirely, old habits die hard. “Alongside the PhD students I’ll keep supervising, a new EngD candidate called Wesley Massij was appointed recently, whom I’ll be taking under my wings for the next two years. This is ‘volunteer work’, but the topic is too fun not to do it.”

That topic is nature-inclusive construction. “Paying attention to plants, birds, insects, and bats. The latter aren’t doing well. They mainly live in cavity walls and those are often filled up with insulation material these days.” Many municipalities are putting up bat boxes, but those don’t cut it because they get way too cold in winter, says Moonen.

Together with honors students, he came up with a solution that is as pragmatic as it is creative: bat boxes on transformer boxes. “Due to the increasing number of charging stations for electrical cars, there are more and more of those.” Those electricity boxes give off heat, allowing the bats to sleep at a comfortable temperature. “A bat box with underfloor heating, if you will.”

A smart, slightly weird, and inspiring idea, of the kind that only Faas Moonen can come up with and turn into a reality. TU/e and the bat population can count themselves lucky they can still take advantage of this for a while longer.

Role models

Who were Faas Moonen’s biggest role models? “During my studies, these were mainly my thesis supervisor Joop van Ploeg, a ‘woodworm’ if ever there was one, and my ‘concrete prof’ Jan Siebelink, because he was so considerate of students. He would always be up for a quick chat with you in the hallway and remember what you told him. He gave you the feeling that he thought you mattered as a person, which is an example I’ve tried to follow as a teacher.”

During his time as a program director, Moonen learned a lot from Jan Westra, who was the dean of the Department of the Built Environment at the time. “Relying on your own moral compass, for example, but also practical ways of getting what you want. For example, don’t ask the question if you don’t want to hear the answer. Just start doing what you want to do and see what happens. Quality will out, always.”

Discussion