Should students be better educated about student loans?

It turns out you automatically accept all terms and conditions when you use DigiD

Taking out a student loan from the Education Executive Agency (DUO) is easy as one-two-three. At the same time, there’s a duty of care for creditors in the Netherlands. Has DUO actually fulfilled this duty of care? Student Jurre Wolters thinks it hasn’t, but DUO says its duty of care is different because it is not a ‘creditor’ as defined in Title 2a of Book 7 of the Dutch Civil Code and ‘provider’ as defined in the Financial Supervision Act.

Ever since the new interest rates for student loans were announced earlier this month, students have been more concerned with the consequences of borrowing. As many as 1.6 million people in the Netherlands have a student debt, averaging 17.8 thousand euros (figures in early 2024). The total debt amounts to 29 billion euros. Students always receive notification about the new interest rate on student loans from DUO in October. This rate is reset annually by the government.

The interest rate for 2025 is 2.57 percent for students who pay back the debt in 35 years. That interest rate is about the same as it is now (2.56 percent).

Negative interest

DUO could have been in a pickle a few years back when the negative interest rate was introduced, as this would technically have meant students would receive interest when borrowing money. Shortly before that – in 2015 – the law was changed, however, to state that the interest rate must be at least 0 percent. Former minister of education, culture, and science Robbert Dijkgraaf also confirmed this when writing up the budget of the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science (VIII) for the year 2024, in response to questions by former MP Peter Kwint (SP party).

Duty of care

In the Netherlands, there is a duty of care for creditors. This means they must educated people about the consequences of taking out a loan and make inquiries about a person’s creditworthiness. In other words, someone who wants to take out a loan must understand what that means and what the consequences are. And that person should also not be loaned more than they will reasonably be able to pay back over time.

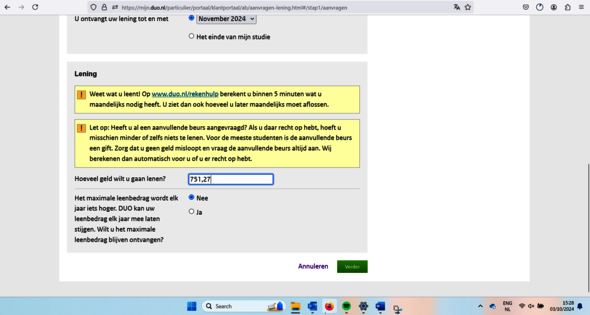

Electrical Engineering master’s student Jurre Wolters believes that DUO does not adequately educate students and thus does not fulfill its duty of care. “Even a phone store where you buy a phone on credit is better at educating you. And that might involve about 1,000 euros. A student debt averages 17.1 thousand euros.” He shows an example of the process of taking out a loan at DUO and at a phone store. The warning at the phone store is clearly more extensive and compelling.

DUO itself states that ‘the granting of student loans takes place on the basis of the Student Finance Act 2000 and therefore DUO is not a ‘creditor’ as defined in Title 2a of Book 7 of the Dutch Civil Code and a ‘provider’ as defined in the Financial Supervision Act. DUO does have a duty of care and that duty consists of providing ‘appropriate support’ in physical and digital contact with the customer. This duty of care follows from the General Administrative Law Act and principles of proper administration.’

Wolters: “I particularly resent the fact that you can indicate to DUO that you always want to borrow the maximum amount and that this loan is then automatically increased for you every year, based on inflation. It’s made very easy for you without warning.” Wolters also shows an example text from the DUO website about applying for a loan. “There’s just a short bit on paying back with interest. That’s not enough to meet the duty of care.” Wolters calls DUO’s customer service to check; an employee confirms to him that he’s right about this not really meeting the duty of care and that it’s too easy to take out a loan.

Wolters recorded this conversation and confronted DUO with it, who then indicated that he wasn’t allowed to publish it just like that and that there is case law about this. Which, incidentally, is true: making a recording for personal use is allowed, even if you haven’t indicated it in advance. But you can’t publish it just like that. Cursor asked DUO about this employee’s answer. The agency says that ‘compared to a bank, taking out a loan from the government is indeed easier. It’s a balance between educating students so they borrow consciously and not making it overly complicated if they do make that conscious decision.’

The Electrical Engineering student has barely any student debt himself, but is concerned about his fellow students. “My father is a mortgage broker, so I know quite a bit about the duty of care of creditors. I saw many of my fellow students max out their loans and be very surprised when the interest rate was suddenly no longer 0 percent. That’s actually weird, for everyone to be so surprised, because if they were properly educated by DUO – part of the duty of care – they wouldn’t be.”

Lawsuit against the state

Many students did not expect to pay any interest at all on their student loans. For years, the interest rate stood at 0 percent, before slowly starting to increase. In 2023, the interest rate was changed from 0.46 to 2.56 (estimated) for 2024, causing a lot of commotion among students. Legal Advice Wanted is suing the state for breaking that 0 percent promise.

However, are there any written records of this 0 percent promise? Both Wolters and Cursor did not manage to find anything of the sort. So how did this idea become so common among students?

An article about the commotion among students in national daily AD stated the following: ‘According to LAW founder Robin Bosch, the state has suggested that interest rates would remain at zero percent for years. Former education minister Ingrid van Engelshoven (D66 party) said several times in the House of Representatives that loan anxiety is unnecessary and that students can pay back under social conditions. The slogan Let op! Geld lenen kost geld (Beware! Borrowing money costs money), which must be used compulsorily in all advertisements for loans, was absent across the board, according to the unions. “We advised DUO to include it, but they said they didn’t think it was necessary. And now look what happened,” Ait Abderrahman argues.’

If LAW wins, what will that precedent mean for all students in the Netherlands? LAW did not respond to questions from Cursor. We also asked DUO how it views LAW’s lawsuit, to which the agency responded as follows: ‘So far we haven’t heard anything about it, but should it come to a lawsuit we’ll be confident about the outcome.’

Government bond

So, when you borrow money for your studies, you borrow from the government. But it’s not the government that fronts you the money: it borrows it in turn. So it’s a government bond. ‘The interest on student debts depends on what the Dutch state pays for loans,’ the Higher Education Press Agency reported in 2015 . ‘The rate is reset annually by DUO, so in 2016 it is 0.01 percent. In 2015, the interest rate was also exceptionally low. Then it was at 0.12 percent.’ How interest rates are set and for what period they are fixed is regulated in the Student Finance Act 2000.

This, then, is the reality of the situation. Could the commotion among students have been avoided if DUO had better educated students? And could better education have resulted in students borrowing less? As for properly educating people, DUO believes it is already making efforts to do so. ‘As a public service provider, we always try to educate students as well as possible about what the consequences are if you take out a loan. And that paying interest on a loan is part of the deal. This is a standard part of our personal communication towards students, for instance in emails and student loan applications, as well as when we give them general communication and information via social media and the website. After all, we think it’s very important that students are well informed so they can make conscious financial choices.’

Kifid

In the Netherlands, you have the Dutch Institute for Financial Disputes (Kifid). Here, they deal with cases where someone indicates they’ve borrowed too much money and they’re not able to shoulder this burden. This is different from paying back a student loan. After all, your repayments are based on what you can afford, and if you have any debt remaining after your repayment period it is cancelled. The Kifid website states the following: ‘The Supreme Court has established that the creditor has a duty of care to avoid excessive lending, regardless of the help of an intermediary (if any). The creditor itself remains responsible for making inquiries or verifying data before deciding on the loan to be granted.’

On the website of the Dutch government, the following is stated about the duty of care: ‘Have you suffered damages because the creditor informed you too late? Then you can recover those damages from the creditor’. Does this include DUO’s allegedly faulty information and its changing the interest rate from 0 percent? Cursor asked questions about this to the Ministry of Education, but it didn’t respond.

DUO does not fall under the supervision of the Dutch Authority for the Financial Markets (AFM). “The Authority for the Financial Markets only supervises financial enterprises and their duty of care under the Financial Supervision Act,” the AFM indicates. “DUO is not a financial enterprise but an implementing organization of the central government. We therefore have no authority or insight in student loans from DUO (and the information provided in this regard).”

The fact that DUO is not subject to AFM supervision does not mean that you as a student have nowhere to go, nor that there’s no supervision. “Any interested party who is of the opinion that DUO is not complying with the law (or duty of care) can turn to the courts or the National Ombudsman,” DUO indicates. “In addition, DUO is supervised first and foremost by the Ministry of Education, but the Senate and House of Representatives and the Central Government Audit Service also exercise supervision. In addition, the National Ombudsman can take the initiative to launch an investigation of its own. This also applies to the Dutch Data Protection Authority when it comes to how DUO deals with student privacy.”

Improvement on the website

The press release about the interest rate update by DUO also states that there’s now more information on duo.nl. ‘By way of text and video, students (and former students) can already see whether they will have to deal with the new interest rate next year and how it works. In addition, the calculation tool has been further expanded with the possibility to see how the decrease or increase of the interest rate affects the total student debt.’

DUO also indicated to Wolters early this year ‘that you no longer have a check mark for ‘maximum’ borrowing, but that you have to enter an amount (you can use the calculator to see if and how much you might need to borrow). And we now have the supplementary grant turned on by default so students don’t have to borrow as much (in theory).’ Wolters indicates that this is not correct: “The checkbox, or actually a yes/no question, is still there,” he informs us, having checked just this month.

In October, all students will be notified about their student loans and interest rates in 2025. Former students who are already paying back their student debt will receive the notification in November. In addition, students and those already paying back their debt can view their details in Mijn DUO.

Automatic approval via DigiD

“Students don’t even have to sign anything when they take out a loan from DUO,” Wolters knows from experience. “It would already contribute to their awareness if they did have to. Because the fact is that your interest amount is not fixed for the period you borrow and pay back, but will be adjusted in the interim.” Incidentally, those conditions do appear to exist. DUO itself stated the following to Wolters about this: “Legally, this is laid down in the Student Finance Act 2000, which passed a democratic vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. The conditions for borrowing can be found in the Act and on our site. As they are logged into Mijn DUO, students accept the terms and conditions via DigiD. This makes things legally valid.”

Whether the students acquire clear knowledge of the procedure in so doing is doubtful, since it is not mentioned during the application. “An agreement is not required: it is not a civil law, but an administrative law provision for which you can apply. There are conditions attached to this, however, as indicated on our site,” DUO says to Wolters in closing.

When asked why DUO still doesn’t clearly refer to the conditions – for example by means of a hyperlink – that students accept by virtue of being logged in with DigiD, the agency confirms this is a choice, but doesn’t further motivate this choice.

Phone subscription

After Wolters contacted DUO about his findings, he did receive a substantive response (seen by Cursor). DUO thinks the comparison with a phone on credit is not valid. DUO: “The duty of care, as in Wolters’ phone subscription example, is a checklist to determine whether someone may purchase the product or service. We don’t have that option as a government. All we can do is inform students about the consequences of a loan. Since we can’t set the duty of care in advance, we have set the duty of care in the repayment rules in retrospect, so to speak (such as carrying capacity measurement, run-up phase, diversion of the base year, waiver).”

DUO also states that students are regularly informed of interest rate changes through press releases and personal communication, for example by email, as well as a link to a calculation aid when applying. This gives you the option of calculating the consequences of your loan.

“By the way, the comparison with the phone subscription is also somewhat flawed because the repayment of the former starts immediately after the conclusion of the agreement (i.e., based on current income and fixed expenses). Moreover, repayments aren’t based on affordability (as with student loans). There is also no cancellation of any residual debt after 35 years; the debt of a phone subscription remains.”

Wolters: “But the fact that your loan is cancelled after 35 years does not automatically mean that you don’t suffer any consequence from the loan. For one thing, the mortgage you can get is lower (sometimes even much lower), especially for the unlucky generation of students that didn’t get the basic grant. The new generation of students that is getting it has a smaller financial burden and, therefore, a ‘head start’ of about twenty thousand euros in terms of mortgage.”

Awareness

DUO indicated to Wolters that the agency ‘also commissioned further research among the target group to map out their borrowing behavior. Incidentally, the conclusion was that during the study period the target group is not very aware of the consequences of borrowing. That moment comes when they have graduated or when they have to start paying back the loan.’

Cursor asked why extra efforts aren’t made for the exact goal of raising awareness among young people, seeing how DUO’s own research show this is lacking. DUO responded as follows: ‘This certainly remains a continuous point of attention for us. We are always open to suggested improvements. We also test these with actual students and with your youth board.’

Discussion