Having a baby as a PhD candidate: entirely possible

“Your private life doesn’t have to be on pause while you’re getting a PhD.”

Six babies in two years, that’s the new-born count at the Physical Chemistry group. And there’s another one on the way. While most PhD candidates still get slightly stressed about whether they’ll finish their research in the allocated three or four years, the people featured here have felt free enough to fulfill their wish of having children. Why is that? And what can the university do to support more PhD candidates and postdocs who would like to have children?

When Cursor sits down with PhD candidate Lisette Wijkhuijs (30) in the latter’s home, the baby monitor is on the table. The occasional babbling noises from her daughter Emma are the soundtrack to Wijkhuijs’s weekly stay-at-home day. “We go swimming in the morning and I really enjoy that,” she says.

She began her PhD in October 2020, switching to part-time in July 2022. “I’m conducting research into energy storage materials, especially in the form of heat, and I’m also involved in educational development because of the new bachelor’s program at our department. Because of that, I was a bit behind schedule already, and the pregnancy caused some more delays, but that’s okay.” On April 17, 2024, little Emma was born.

Lab work as a stumbling block

PhD candidate Laura van Hazendonk (29) is heavily pregnant when we speak to her. In one week her leave will start and then it won’t be long before she’ll give birth. When you’re pregnant, you’re not allowed to enter the lab for safety reasons. That can cause some delays if you’re a woman and you’re still in your lab phase.

Van Hazendonk: “I do experimental research and develop graphene-based inks for printing electronics. This also involves some lab work, especially in the first few years of my PhD. Now I mostly write, so that limitation doesn’t affect me quite as much. If you do get pregnant in the earlier phase of your PhD, you still have options, such as working with a master’s student who can temporarily take over your lab duties. And it did make the writing process more challenging, because you can’t just quickly do one final control experiment.”

Wijkhuijs also had to deal with this. “I was no longer allowed into the lab, but had a student that could do the lab work for me so I could write. With a little help from others, I kept my PhD on track. All in all, it didn’t feel like everything was on pause.”

Role models

Wanting to have a baby isn’t something you decide overnight. “I did think I wanted a child, although I also had my doubts,” says Van Hazendonk. “But those were more about the timing. My partner understood very well that the impact on me would be greater and supported me. My colleague Mark Vis was also able to help me think things over, because he had been through the process twice. From his more ‘senior’ position, he was also able to give advice on timing and impact on my career.”

Van Hazendonk did miss female role models with children: “The women at uni that I knew with children were often already assistant, associate, or full professors. Those who had ‘already made it in science’ had their children at a later age than me. That does make you think. It would be nice to also see more role models who, like me, had a child during their PhD.”

“I always knew I wanted children,” Wijkhuijs says. “I’ve been with my current husband since 2014. It’s especially hard that you don’t have any examples: there are almost no PhD candidates who have babies. One or two guys maybe, but it’s very different if you’re a woman and you’re having a baby. For one thing, women can’t work in the lab anymore, as opposed to men. And if I were to wait until after my PhD, I’d already be 31. Then you still have to wait until you have a permanent contract. And then you also don’t know if you’ll get pregnant right away, so you might be 33 or 34 when you have your first child. And we would love to have another one. It’s never the ideal time, so just go for it.”

Making choices

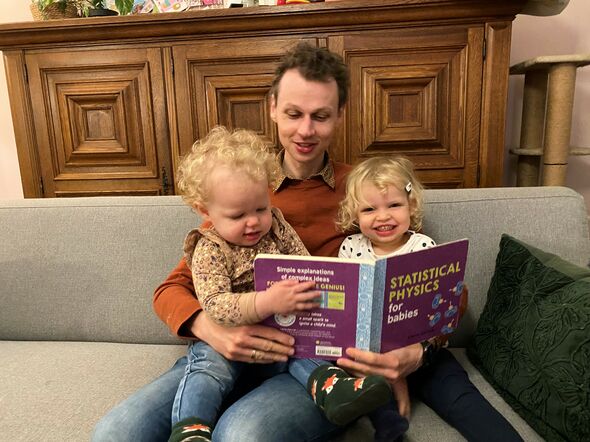

Assistant professor Mark Vis (36) welcomed two daughters into his family in recent years. “Janneke is now 2 and Sietske is 1.” He works with complex mixtures of colloids, polymers, and macromolecules.

“I definitely thought about the consequences of having children as a scientist,” says Vis, “but most of them really only became clear in practice. I joined the group in 2016 as a postdoc. In 2019 I became an assistant professor and in 2022 my first child was born. So I was a little later than Laura and Lisette and already had tenure, but still. You definitely think about the career consequences, but I simply feel my family is more important than getting everything out of my career.”

As a result, Vis is extra happy with his stay-at-home day. Having said that, he also sees that having a day off does not reduce the amount of work. “There’s still a lot to do. You don’t suddenly have fewer PhD candidates to supervise or less teaching to do if you start working one day less. That means it gets tougher to decide what to do and what not to do. Long-term things like grant applications are the first to go. Everything else has immediate priority, such as preparing lectures and supervising PhD candidates. But I get good support from my boss, who has my back and thinks my choice makes sense.”

Telling people

Wijkhuijs: “It was very nice to have the feeling that pregnancy wasn’t a problem in our group. I was a bit tense about telling people I was pregnant. I went to the group head’s office by myself, slightly stressed out because you know the timing is never ideal. But Remco reacted with such enthusiasm when I told him I was pregnant ... he made me feel like it was great news.”

Joy

We asked everyone featured here what having a child has brought them or what they think it will bring them. That question invariably put a huge smile on their faces. “Emma just makes me intensely happy,” says Wijkhuijs. “It’s everything I imagined and more. She was born and suddenly everything felt right. As if something had always been missing and now it was there. She brings an awful lot of happiness and joy, alongside the inevitable but occasional worries.”

“My two little kids give me a lot of joy,” says Vis, smiling from ear to ear. “You get to know yourself: what do I find difficult and what do I like? Besides, it’s so nice to see how excited they get about little things. Yes, they really give me great joy and satisfaction.”

Van Hazendonk can only imagine it for now, but thinks it will give her life a different meaning. “It’s still a little abstract right now, but I think it’s just really beautiful to be able to watch a miniature person grow up.”

Advice to other PhD candidates

Of course, no one that wants a baby knows if they’ll actually be able to conceive. That also came into Van Hazendonk and her partner’s decision to start trying. “The family doctor suspected that I might have PCOS, which would mean my chances of getting pregnant decrease as I get older. And I want to do a postdoc after this. That often takes one or two years: not at all ideal for a pregnancy. So we figured we’d go for it now.”

Van Hazendonk thinks it would help if having a baby during your PhD became more normal. “I honestly think it’s entirely possible. A PhD takes years and I was doing it part time anyway because of my political activities for the GroenLinks party. I also see the advantages: a peer reviewstill takes the same amount of time whether you work part-time or full-time. When you look at it that way, I’m actually losing less time.”

“I wouldn’t advise getting pregnant in the first year of a PhD, which is generally very experiment-driven,” Wijkhuijs says. “But in the third year it’s fine, especially if you have a student to help you out. And make sure to have a proper conversation with your supervisor. For example, you can discuss adding a more theoretical aspect to your project.”

Vis had his first child when he was 34. “In retrospect, I’d have liked to have children earlier. That didn’t happen for all kinds of practical reasons, but I think it would have been nice. So my message to younger PhD candidates is: if you’re both ready, definitely consider it. When you’re younger, you’re a bit more flexible and able to perform on little sleep,” he laughs.

“In any case, I really don’t regret having a baby during my PhD,” Wijkhuijs says. “It won’t stop me from completing it either. And if I were to start my PhD over, I’d do it the same way again.”

Flexibility and understanding

Like her colleagues, Van Hazendonk has been met with flexibility and understanding in her research group. “There were times during my pregnancy when I didn’t feel great, so it was very nice to have that understanding.” During her pregnancy, she came into contact with several PhD candidates from other departments who also had children during their doctoral studies. “So as it turns out, it’s not that uncommon. I really enjoyed hearing about their experiences.”

“The atmosphere in the group makes me feel supported,” says Vis. “I think the group head is largely responsible for this. He (Remco, ed.) has children of his own, which helps. It makes it easier to understand the turbulent times you go through when you have a child. Taking extra time off or working from home because a child is sick is part of the deal. But it’s not always ideal, as lectures basically always have to go through. Fortunately, I have a partner and we do it together.”

Remco Tuinier heads the Physical Chemistry group. Members of this group certainly feel the freedom to make their wish of having children come true. Does Tuinier ever discuss this with colleagues from other groups? “Not TU/e-wide, really. I do talk to the academic staff of the other group that have offices on this corridor. I have noticed they generally think the same way. There are a lot of young parents here in the corridor.”

I did hear at previous employers that when women were pregnant they were told that it wasn’t the right time, that it wasn’t convenient. But it never is

But why is it that people feel that freedom? How do you create that atmosphere? “Maybe it helps how I feel about this issue myself. In my own experience, realizing one’s wish to have children can be challenging. And I did hear at previous employers that when women were pregnant they were told that it wasn’t the right time, that it wasn’t convenient. But it never is.”

“As a manager, I think being a good employer is important. Give people space and freedom so they can flourish. I don’t find it very interesting to focus on whether people at the university are working hard all the time. Rather, I look at the output. I just hope that people feel at liberty to combine their work and private life in a way that suits them. I think they perform best if that’s the case.”

Tuinier does notice concerns among PhD candidates that they won’t be able to complete their dissertation in the allotted time. “You try to reassure them by clearly communicating expectations and using the helicopter view for a moment: where are we now and what still needs to be done, the bigger picture. They tend to like that.”

Nicer environment

How could the university create a nicer environment for PhD candidates or postdocs who would like to have a baby? Wijkhuijs: “In 2021, we were in Grenoble to conduct experiments. That’s when Remco, Mark, Laura, and I talked about our views on having children as PhD candidates. Everyone thought it ought to be possible. Your life doesn’t have to be on pause while you’re getting a PhD. In the end, it’s just a job.”

For Van Hazendonk, more clarity when it comes to rules, rights and options would help. “Take the sixteen weeks of pregnancy leave paid for by the Employees Insurance Agency. If your pregnancy happens in the middle of the experiment-driven phase of your PhD, the delay you incur may exceed your pregnancy leave. What happens then? Removing that uncertainty would be very nice. Because at the same time, I also understand that it’s very difficult for the university if a supervisor has only one Veni grant, for example. Then they have no money to renew your contract.”

In the end, Van Hazendonk’s contract was extended for sixteen weeks without any problems. “But it would be nice if that could be arranged earlier. Remco told me that HR always grants the extension a few weeks before the contract expires, which would have been just after the end of my pregnancy leave. That creates so much uncertainty while you’re on that leave, which isn’t ideal if you’re depending on this income, have to take care of a baby, and don’t know if you’ll still have a job to go back to. I took some effort on my part to get confirmation earlier than usual. But it would help if people proactively thought about this.”

You can’t apply for parental leave until the baby is born, but you want to arrange that early on, because when the baby is born you have other things on your mind

Wijkhuijs: “When I just got pregnant, I wanted to arrange everything properly, but that was quite difficult. I would have liked to have a list of everything that needed to be done, but that didn’t really exist. You can’t apply for parental leave until the baby is born, but you want to arrange that early on, because when the baby is born you have other things on your mind.”

“Procedures don’t always go smoothly,” associate professor Vis vividly recalls. “My parental leave for my first child was going to overlap with my new birth leave (for his second child, ed.), so I wanted to pause the first one because the second one expires earlier, but I couldn’t because the parental leave had already started. It should be possible to make different arrangements, because you’re just entitled to those schemes. Maybe it’s just not that common and the system isn’t geared to it, at least not yet. The leave schemes are complicated and could be clearer and more user-friendly ...”

Handing down baby clothes

Having several babies in the same group in a short time comes with unexpected benefits as well: baby clothes and stuff can be handed down. Van Hazendonk, who is next in line to have a baby, will definitely profit from this. “I was able to take a lot of baby gear off Mark’s hands. A former postdoc gave me lots of baby clothes, as well as a co-sleeper.” She laughs. “That co-sleeper is now group property, haha. It went from an associate professor to a postdoc, and now to me. I actually didn’t have to buy almost anything new. And Mark brought all the stuff to our house because we don’t own a car. It shows how supportive our group is and I’m very pleased about that.”

Discussion